The Oil Patchs Manhattan Project, How to Fix Its Gargantuan Water Problem

huge saltwater pond in the middle of the biggest oil field in the U.S.

They are part of an experiment by Exxon Mobil XOM -1.47% to address one of the

challenges facing frackers in the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico: what to

do with the gargantuan amounts of noxious water they produce alongside crude.

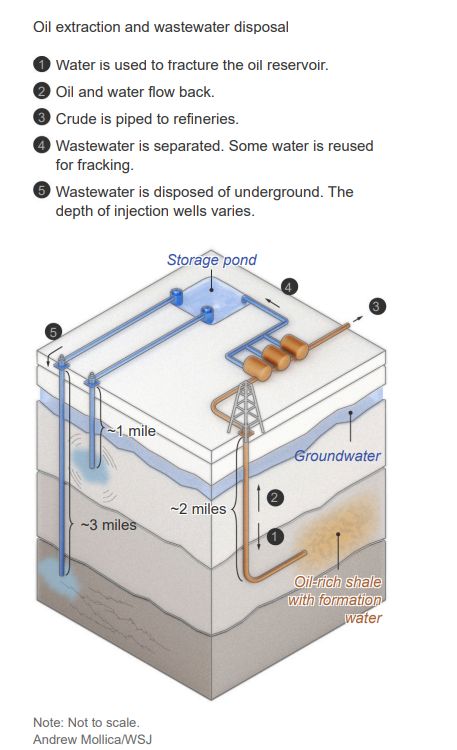

As oil production has jumped to records in recent years, so have water volumes.

Permian producers on average pump about four barrels of water for each barrel of

crude. They have long reinjected it underground, which has caused the ground to

buckle, triggered earthquakes and made drilling more onerous.

Last year, Permian drillers discarded roughly 5.5 billion barrels of water that way,

according to water analytics firm B3 Insight, roughly equivalent to the amount of water

that New York City consumes in about eight months.

Now, companies are investing millions of dollars testing technologies to evaporate the

water faster, and strip it of salt so it can be reused outside the oil patch. They are

crafting plans to release scrubbed water into rivers—and hope to one day provide it to

farmers and municipalities.

“We need a Manhattan Project to deal with the produced water,” said Kirk Edwards, an

oil executive and former chairman of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association,

referring to the U.S. effort to produce the first atomic bomb.

The Trump adminis

Companies in recent years have made strides in treating the brine and recycling it for their operations, but more water flows back to the surface than they can use. Meanwhile, the volumes of liquid they can pump in the ground have shrunk as companies have started to run out of underground space, and regulators have imposed limits on disposal to prevent earthquakes.

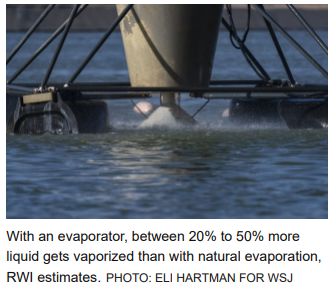

Enter the evaporators. Exxon, the largest Permian producer, started testing the machines about a year ago as a pilot project. The devices, manufactured by Coloradobased RWI Enhanced Evaporation, blow air down on the pond of produced water to create droplets and ripples, which speeds up the evaporation process. One machine costs about $46,000 and consumes about as much electricity as a wet-dry vacuum cleaner.

RWI estimates that between 20% to 50% more liquid gets vaporized that way compared with natural evaporation. Wind, heat, humidity and sunlight all have a bearing on how much water is vaporized.

The technology is no panacea: While an injection well typically guzzles between 10,000 and 25,000 barrels of water a day, an evaporator working in optimal conditions vaporizes about 32 barrels an hour, according to Robert Ballantyne, a senior vice president at RWI.

Rich Dealy, who oversees Exxon Mobil’s Permian operations, said the pilot project is just one of several options the company is studying to address the water issue. It is also looking at piping water to the fringes of the Permian, where there is more underground space available, as well as at desalination.

“How do we get surface disposal is kind of the next big step,” said Dealy.

Exxon says it aims to have a commercial-size desalination facility operating in the Permian by the end of next year. Energy-services firm Tetra Technologies TTI -6.40 % and driller EOG Resources EOG -1.26% last month announced they were commencing a pilot project to desalinate produced water from the Permian.

Although it costs about twice as much to desalinate produced water than it does injecting it down a well, the companies are hopeful they can bring the cost down.

“Everybody is getting to the point now where this can be done effectively, and it can be done cost-effectively,” said Robert Crain, an executive vice president at Texas Pacific Water Resources, a water-focused unit of landowner Texas Pacific Land . TPL -3.82 %

The firm has tested desalination technology at a 20-barrel-a-day pilot project outside Midland. One common technique to remove salt is to run the liquid through membranes that hold back solids, but oil-field water, which is much saltier than seawater, takes a toll on the material. Instead, Crain’s company freezes the brew, which helps separate saltwater from fresher water.

Crain’s goal is to bring the cost of purifying a barrel down to 75 cents, which is slightly more than what it costs to flush it down a well. Texas Pacific Water Resources has begun constructing a $25 million desalination facility with an initial capacity of 10,000 barrels of produced water a day, and plans to build a Permian plant 10 times bigger next year.

Texas Pacific Water Resources has tested for hundreds more contaminants in the desalinated water than what is required by regulators, said Adrianne Lopez, the company’s research and development manager. She said the firm passed multiple rounds of a lab test to determine whether the purified water will hurt living aquatic organisms.

“We don’t want to put something on the ground or in a river that is essentially going to cause harm or get us in trouble,” she said.